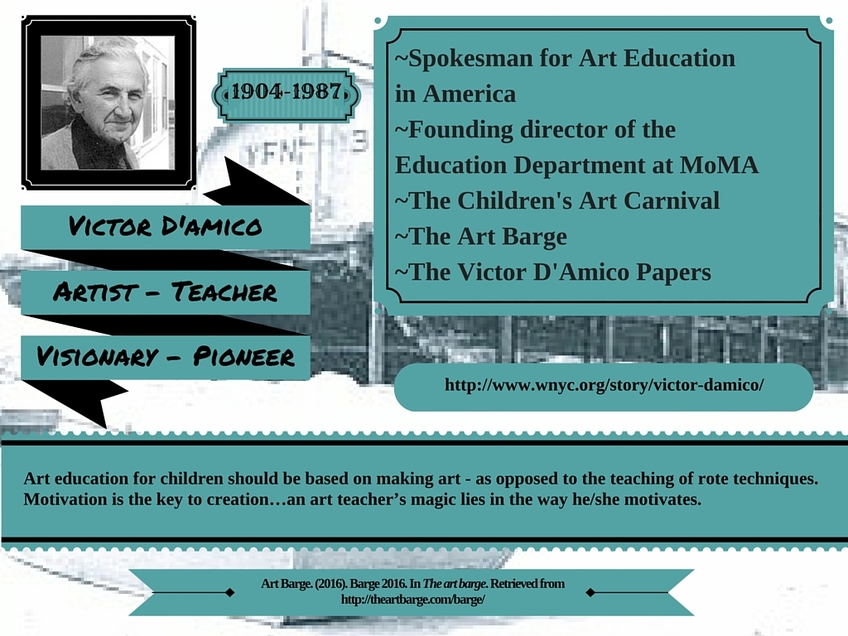

*Victor D'Amico's photograph was reproduced from The Art Barge website.

Victor D’Amico, (dah-mē-cō) was a remarkable artist, teacher, visionary and pioneer of modern art education. He was considered a spokesman for art education in America and was the founding director of the Education Department at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) for more than 30 years (1937-1970). While at MoMA D’Amico created innovative learning environments for people of all ages, as well as outreach programs for the community. He also offered free art classes for any teacher from public schools.

D’Amico’s Philosophy

D’Amico “felt the role of the museum was that of a laboratory for the development of creative teaching practices. And thus, his programs became his experiments” (Rasmussen, 2010, para. 8). He used his thirty years with MoMA to cultivate his philosophy of art education.

“His philosophy was based on a fundamental faith in the creative potential in every man, woman, and child” (Art Barge, 2016, Barge para 1). D’Amico believed every individual to be endowed with “a unique creative personality as distinctive as one’s fingerprints, voice print, or personal characteristics” (Raunft, 2001, p. 6). In an interview by Bowman (1969) on WNYC D’Amico stated,

Victor D’Amico, (dah-mē-cō) was a remarkable artist, teacher, visionary and pioneer of modern art education. He was considered a spokesman for art education in America and was the founding director of the Education Department at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) for more than 30 years (1937-1970). While at MoMA D’Amico created innovative learning environments for people of all ages, as well as outreach programs for the community. He also offered free art classes for any teacher from public schools.

D’Amico’s Philosophy

D’Amico “felt the role of the museum was that of a laboratory for the development of creative teaching practices. And thus, his programs became his experiments” (Rasmussen, 2010, para. 8). He used his thirty years with MoMA to cultivate his philosophy of art education.

“His philosophy was based on a fundamental faith in the creative potential in every man, woman, and child” (Art Barge, 2016, Barge para 1). D’Amico believed every individual to be endowed with “a unique creative personality as distinctive as one’s fingerprints, voice print, or personal characteristics” (Raunft, 2001, p. 6). In an interview by Bowman (1969) on WNYC D’Amico stated,

Talented is probably the most misused word in our profession. When one says talented, he means there are those children who have a gift and those children who do not. I disagree. I know there is a great deal of research on this particular problem and no real research has come out that says that this child is talented and that one is not. I’ve taught them long enough to know that all children have a measure of talent.

It was D’Amico’s idea that talent could be brought out in all individuals through proper instruction and motivation.

D’Amico believed art education should be based on making art and the “cultivation of creative artistic vitality” (Rasmussen, 2010b, p. 461). He understood that children have no inhibitions when it comes to artmaking. With encouragement and time to explore, they would freely express their ideas (Newsom & Silver, 1979, p. 59). They naturally use art as a personal language and by nature are free and spontaneous in their expression.

D'Amico considered the "fundamentals to be the development of individuality and the awareness and sensitivity to aesthetic values in works of art, in human relations, and in one’s environment" (D'Amico, 1960, p. 14). Children should see themselves as artists and work as artists. Their art should be about their lives, their families, and their experiences (D’Amico, 1953). They should spend time exploring museums and their environment, looking for things to paint and things to create.

The Role of the Teacher

In an interview with Bowman (1969) on WNYC, D’Amico shared that children, as well as adults, “need the guidance of experienced and sensitive teachers.” In his thinking, an exceptional art educator understands the concepts of psychological growth, both creative and general. Most important, they are able "to stimulate and develop the creative interests of others and to communicate the aesthetic values that underlie all creative achievement" (D'Amico, 1960, p. 9). They have a positive attitude, respect for individuality, and are devoted to excellence and design and craftsmanship.

D’Amico thought an art teacher’s magic lies in the way he/she motivates students. Stimulating the students’ interests and probing for individual thinking and solutions are key components. The teacher should adjust activities to the student’s ability and experience and lead each child to rise above his last attempt, thus assuring growth and progress.

D’Amico believed creative teaching gives children the opportunity and time to explore their world of experience. It accepts and respects a child’s creation, recognizing that emphasis is not on the churning out of art products that are uniform and aesthetically pleasing. It is on the growth of the creative spirit (Sahasrabudhe, 1994). It encourages students to give expression to the experiences and to find form for their discoveries. It encourages free and uncluttered (from adult demand and social pressures) expression.

The Learning Environment

D’Amico (1960) held firm to the belief that creative teaching involves setting up the proper learning environment, one that evokes interest and stimulates individual expression. This is seen in D’Amico’s most widely acclaimed and influential program, the Children’s Art Carnival. The program was an elaborate environment of toys, workstations and art materials where children could make paintings, sculptures and collages.

Children began their adventure at the Children’s Art Carnival in a specified space, called the Inspiration Area. In this area children were “stimulated to think creatively” while being “oriented to the fundamentals of design without words or dogma of any kind” (D’Amico, 1960, p. 35). The space was devised to motivate creative thinking with the use of unique toys that involved “the child in aesthetic concepts of color, texture, and rhythm” (D’Amico, 1960, p. 35). D’Amico and other artists and designers specifically designed the toys for the space. The walls of the Inspiration Area were painted in blues and greens and the room was dimly light to create a world of magic and fantasy. Toys had lights focused on them from above or they were lit from within. Music played in the background.

After visiting the Inspiration Area, children entered the Studio Workshop where three centers were available for creating art. The space was brightly lit and the walls were painted in bright, warm colors. Tables, easels, and work areas were painted in contrasting colors. An abundance of supplies were available for students to explore and experiment with: paint, brushes, tape, glue, scissors, feathers, pipe cleaners, sequins, colored and patterned papers, cloth, etc. Special care was given to the arrangement of furniture, supplies, and decorations. Texture, glitz, and color were used to inspire creativity.

According to Rasmussen (2010b) the Children’s Art Carnival tested D’Amico’s ideas about the development of creative environments and the selection and presentation of materials. These areas inspired children of various development levels and learning styles while addressing combinations of visual, tactile, and kinesthetic experiences. They engaged children individually or cooperatively in small groups of two to three.

The Curriculum

D’Amico’s (1953) curriculum had two aspects to it. Initially, he sought for children to recognize and reflect on their own experiences for inspiration. Then, technique and instruction were introduced based upon the children’s development and maturity according to their needs and interests. Lessons were prepared and organized in a coherent and logical fashion.

According to D’Amico (1960) a responsive curriculum needed to include: a) both two- and three-dimensional expression-painting, clay work, collage, and construction; b) tempera, watercolor, colored chalks, inks, non-firing moist clay, various materials for building and collages such as cardboard, construction paper, tissue paper, material swatches, popsicle sticks, swab sticks, buttons, yarn, bottle caps, etc.; c) individual as well as collaborative projects; d) examples of various styles and artists to motivate creative activity; and e) trips to local museums.

D’Amico also encouraged the exploration of the student’s environment. He believed an awareness of local materials gave the children the opportunity to create something of their own while making them conscious of their individual environment (Bowman, 1969). According to Daichendt (2010), D’Amico’s curriculum clearly demonstrated that he placed importance on the individual child.

Educating Parents

Another interesting aspect of D’Amico’s philosophy was his means of educating the parents. He held parent-children classes where fathers and mothers could paint, model clay, or create collages with their children (D’Amico, 1960). This provided D’Amico an opportunity to give advice to parents on how to develop their children’s creative interests at home and also offered a time where parents could actually see their children’s creative minds at work. The class sizes were limited and the children in each class were close in age. Parents were advised not to do the work for the children or to make suggestions that might hinder the children’s own ideas and efforts (D’Amico, 1960). The parents and children would work on different projects but side by side or directly across from each other.

Quotes by Victor D'Amico

"The arts are a humanizing force and their major function is to vitalize living."

“Talented is a misused word…all children have a measure of talent.".

“Motivation is the key to creation…an art teacher’s magic lies in the way he/she motivates.”

“Painting is a natural expression of childhood, and one of the best media for stimulating creative response. Its fluid movement and ease of control make it pleasing to most children. It encourages spontaneity and originality in the most stubborn and inhibited nature. With the proper attention and direction, the tense, the academic, and the timid can be reborn through painting into a world of freedom and satisfaction."

“The art teacher is vital to the education of the individual; his selection and preparation are, therefore, of great importance.”

Other Accomplishments

Victor D’Amico was an active member of Progressive Education Association, chairing the committee that produced The Visual Arts in General Education in 1940, a report on the function of art in secondary education.

In 1943, D’Amico helped establish the National Committee on Art Education as a means to provide leadership for excellence in creative art teaching without making compromises.

He was a prolific author on the subject of art education and received numerous honors and awards, including an honorary doctorate of fine arts at the University of Pennsylvania in 1964.

References

Art Barge. (2015). Victor D'Amico Institute of art, the Art Barge2015, In The art barge. [Web log comment] Retrieved from

http://theartbarge.com/barge/

The Children's Art Carnival. (2015). In NYC Service. [Web log comment]. Retrieved from

http://www.nycservice.org/organizations/861

Bowman, R. (Producer). (1969, November). Views on art. [Audio podcast]. Retrieved from http://www.wnyc.org/story/victor-

damico/

D’Amico, V. (1953). Creative teaching in art. Scranton, PA: International Textbook company.

D'Amico, V. (1960). Experiments in Creative Art. New York, NY: Museum of Modern Art.

Newsom, B. Y., & Silver, A. Z. (Eds.). (1978). The education mission of the Museum of Modern Art. In The Art Museum as Educator (pp.

56-62). Berkley, CA: University of California Press.Retrieved from

https://books.google.com/booksid=xbG_W0mevmIC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_

r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

Rasmussen, B. (2010a, July 25). Mining modern museum education: Briley Rasmussen on Victor D’Amico. Inside Out. Retrieved from

http://www.moma.org/explore/inside_out/2010/06/25/mining-modern-museum-education-briley-rasmussen-on-victor-d-

amico

Rasmussen, B. (2010b, October). The laboratory on 53rd street: Victor D’Amico and the Museum of Modern Art, 1937-1969. Curator,

53(4), 451-464. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.2151-6952.2010.00046.x/full

Raunft, R. (2001). Victor D'Amico. The Autobiographical Lectures of Some Prominent Art Educators. (47-58). Reston, VA: National Art

Education Association.

Sahasrabudhe, P. (1994, January). Victor D’Amico: expressing the creative.School Arts, 93(4), p. 34. Retrieved from

http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.dop=GRGM&u=gain40375&id=GALE%7CA14898297&v=2.1&it=r&sid=summon&userGroup=

gain40375&authCount=1

D’Amico believed art education should be based on making art and the “cultivation of creative artistic vitality” (Rasmussen, 2010b, p. 461). He understood that children have no inhibitions when it comes to artmaking. With encouragement and time to explore, they would freely express their ideas (Newsom & Silver, 1979, p. 59). They naturally use art as a personal language and by nature are free and spontaneous in their expression.

D'Amico considered the "fundamentals to be the development of individuality and the awareness and sensitivity to aesthetic values in works of art, in human relations, and in one’s environment" (D'Amico, 1960, p. 14). Children should see themselves as artists and work as artists. Their art should be about their lives, their families, and their experiences (D’Amico, 1953). They should spend time exploring museums and their environment, looking for things to paint and things to create.

The Role of the Teacher

In an interview with Bowman (1969) on WNYC, D’Amico shared that children, as well as adults, “need the guidance of experienced and sensitive teachers.” In his thinking, an exceptional art educator understands the concepts of psychological growth, both creative and general. Most important, they are able "to stimulate and develop the creative interests of others and to communicate the aesthetic values that underlie all creative achievement" (D'Amico, 1960, p. 9). They have a positive attitude, respect for individuality, and are devoted to excellence and design and craftsmanship.

D’Amico thought an art teacher’s magic lies in the way he/she motivates students. Stimulating the students’ interests and probing for individual thinking and solutions are key components. The teacher should adjust activities to the student’s ability and experience and lead each child to rise above his last attempt, thus assuring growth and progress.

D’Amico believed creative teaching gives children the opportunity and time to explore their world of experience. It accepts and respects a child’s creation, recognizing that emphasis is not on the churning out of art products that are uniform and aesthetically pleasing. It is on the growth of the creative spirit (Sahasrabudhe, 1994). It encourages students to give expression to the experiences and to find form for their discoveries. It encourages free and uncluttered (from adult demand and social pressures) expression.

The Learning Environment

D’Amico (1960) held firm to the belief that creative teaching involves setting up the proper learning environment, one that evokes interest and stimulates individual expression. This is seen in D’Amico’s most widely acclaimed and influential program, the Children’s Art Carnival. The program was an elaborate environment of toys, workstations and art materials where children could make paintings, sculptures and collages.

Children began their adventure at the Children’s Art Carnival in a specified space, called the Inspiration Area. In this area children were “stimulated to think creatively” while being “oriented to the fundamentals of design without words or dogma of any kind” (D’Amico, 1960, p. 35). The space was devised to motivate creative thinking with the use of unique toys that involved “the child in aesthetic concepts of color, texture, and rhythm” (D’Amico, 1960, p. 35). D’Amico and other artists and designers specifically designed the toys for the space. The walls of the Inspiration Area were painted in blues and greens and the room was dimly light to create a world of magic and fantasy. Toys had lights focused on them from above or they were lit from within. Music played in the background.

After visiting the Inspiration Area, children entered the Studio Workshop where three centers were available for creating art. The space was brightly lit and the walls were painted in bright, warm colors. Tables, easels, and work areas were painted in contrasting colors. An abundance of supplies were available for students to explore and experiment with: paint, brushes, tape, glue, scissors, feathers, pipe cleaners, sequins, colored and patterned papers, cloth, etc. Special care was given to the arrangement of furniture, supplies, and decorations. Texture, glitz, and color were used to inspire creativity.

According to Rasmussen (2010b) the Children’s Art Carnival tested D’Amico’s ideas about the development of creative environments and the selection and presentation of materials. These areas inspired children of various development levels and learning styles while addressing combinations of visual, tactile, and kinesthetic experiences. They engaged children individually or cooperatively in small groups of two to three.

The Curriculum

D’Amico’s (1953) curriculum had two aspects to it. Initially, he sought for children to recognize and reflect on their own experiences for inspiration. Then, technique and instruction were introduced based upon the children’s development and maturity according to their needs and interests. Lessons were prepared and organized in a coherent and logical fashion.

According to D’Amico (1960) a responsive curriculum needed to include: a) both two- and three-dimensional expression-painting, clay work, collage, and construction; b) tempera, watercolor, colored chalks, inks, non-firing moist clay, various materials for building and collages such as cardboard, construction paper, tissue paper, material swatches, popsicle sticks, swab sticks, buttons, yarn, bottle caps, etc.; c) individual as well as collaborative projects; d) examples of various styles and artists to motivate creative activity; and e) trips to local museums.

D’Amico also encouraged the exploration of the student’s environment. He believed an awareness of local materials gave the children the opportunity to create something of their own while making them conscious of their individual environment (Bowman, 1969). According to Daichendt (2010), D’Amico’s curriculum clearly demonstrated that he placed importance on the individual child.

Educating Parents

Another interesting aspect of D’Amico’s philosophy was his means of educating the parents. He held parent-children classes where fathers and mothers could paint, model clay, or create collages with their children (D’Amico, 1960). This provided D’Amico an opportunity to give advice to parents on how to develop their children’s creative interests at home and also offered a time where parents could actually see their children’s creative minds at work. The class sizes were limited and the children in each class were close in age. Parents were advised not to do the work for the children or to make suggestions that might hinder the children’s own ideas and efforts (D’Amico, 1960). The parents and children would work on different projects but side by side or directly across from each other.

Quotes by Victor D'Amico

"The arts are a humanizing force and their major function is to vitalize living."

“Talented is a misused word…all children have a measure of talent.".

“Motivation is the key to creation…an art teacher’s magic lies in the way he/she motivates.”

“Painting is a natural expression of childhood, and one of the best media for stimulating creative response. Its fluid movement and ease of control make it pleasing to most children. It encourages spontaneity and originality in the most stubborn and inhibited nature. With the proper attention and direction, the tense, the academic, and the timid can be reborn through painting into a world of freedom and satisfaction."

“The art teacher is vital to the education of the individual; his selection and preparation are, therefore, of great importance.”

Other Accomplishments

Victor D’Amico was an active member of Progressive Education Association, chairing the committee that produced The Visual Arts in General Education in 1940, a report on the function of art in secondary education.

In 1943, D’Amico helped establish the National Committee on Art Education as a means to provide leadership for excellence in creative art teaching without making compromises.

He was a prolific author on the subject of art education and received numerous honors and awards, including an honorary doctorate of fine arts at the University of Pennsylvania in 1964.

References

Art Barge. (2015). Victor D'Amico Institute of art, the Art Barge2015, In The art barge. [Web log comment] Retrieved from

http://theartbarge.com/barge/

The Children's Art Carnival. (2015). In NYC Service. [Web log comment]. Retrieved from

http://www.nycservice.org/organizations/861

Bowman, R. (Producer). (1969, November). Views on art. [Audio podcast]. Retrieved from http://www.wnyc.org/story/victor-

damico/

D’Amico, V. (1953). Creative teaching in art. Scranton, PA: International Textbook company.

D'Amico, V. (1960). Experiments in Creative Art. New York, NY: Museum of Modern Art.

Newsom, B. Y., & Silver, A. Z. (Eds.). (1978). The education mission of the Museum of Modern Art. In The Art Museum as Educator (pp.

56-62). Berkley, CA: University of California Press.Retrieved from

https://books.google.com/booksid=xbG_W0mevmIC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_

r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

Rasmussen, B. (2010a, July 25). Mining modern museum education: Briley Rasmussen on Victor D’Amico. Inside Out. Retrieved from

http://www.moma.org/explore/inside_out/2010/06/25/mining-modern-museum-education-briley-rasmussen-on-victor-d-

amico

Rasmussen, B. (2010b, October). The laboratory on 53rd street: Victor D’Amico and the Museum of Modern Art, 1937-1969. Curator,

53(4), 451-464. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.2151-6952.2010.00046.x/full

Raunft, R. (2001). Victor D'Amico. The Autobiographical Lectures of Some Prominent Art Educators. (47-58). Reston, VA: National Art

Education Association.

Sahasrabudhe, P. (1994, January). Victor D’Amico: expressing the creative.School Arts, 93(4), p. 34. Retrieved from

http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.dop=GRGM&u=gain40375&id=GALE%7CA14898297&v=2.1&it=r&sid=summon&userGroup=

gain40375&authCount=1